It’s not eating enough!

By Marisa Michael, MSc, RDN, CSSD

Registered dietitian and board certified specialist in sports dietetics

There’s a lot of nutrition advice out there for climbers. Some of it is better than others. It can get really granular, from how many grams of protein to eat to what supplement to use.

But there is one overarching goal that many climbers are missing: eating enough food! If you think of nutrition strategy as a whole, some things should be prioritized first before others are implemented.

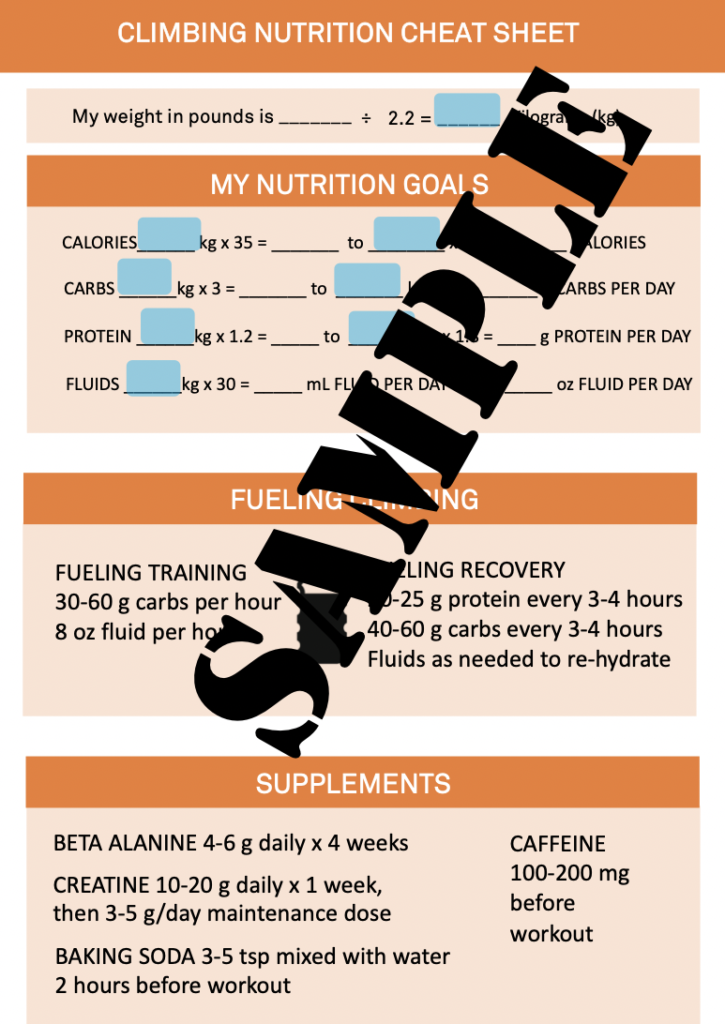

At the top of the list is getting enough overall energy intake. Next up is the macronutrient split. Then meal timing and fueling around workouts, micronutrients, and finally supplements. Unfortunately, many climbers prioritize supplements or protein without even considering that they may be under-eating.

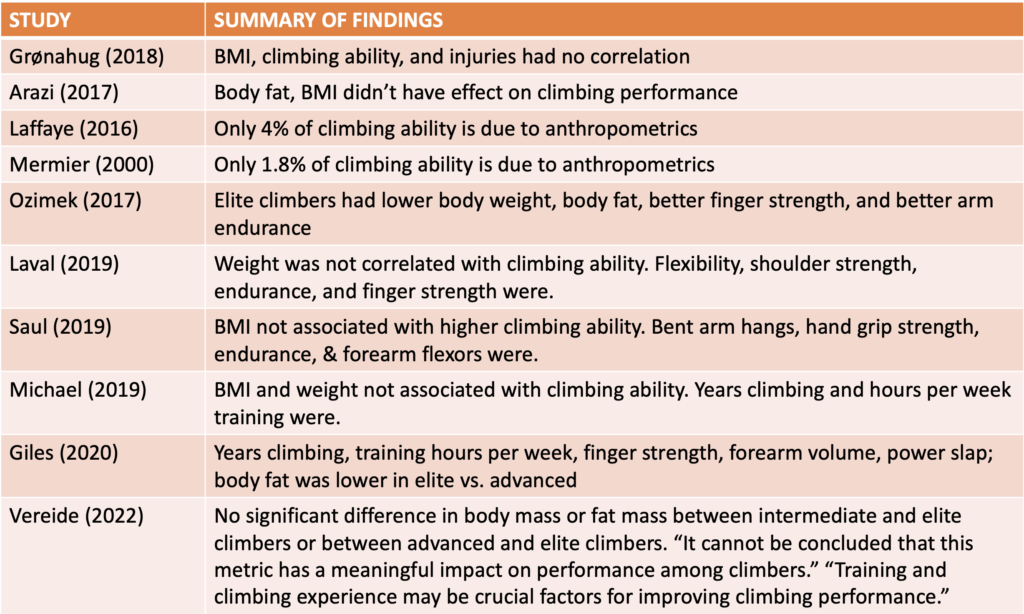

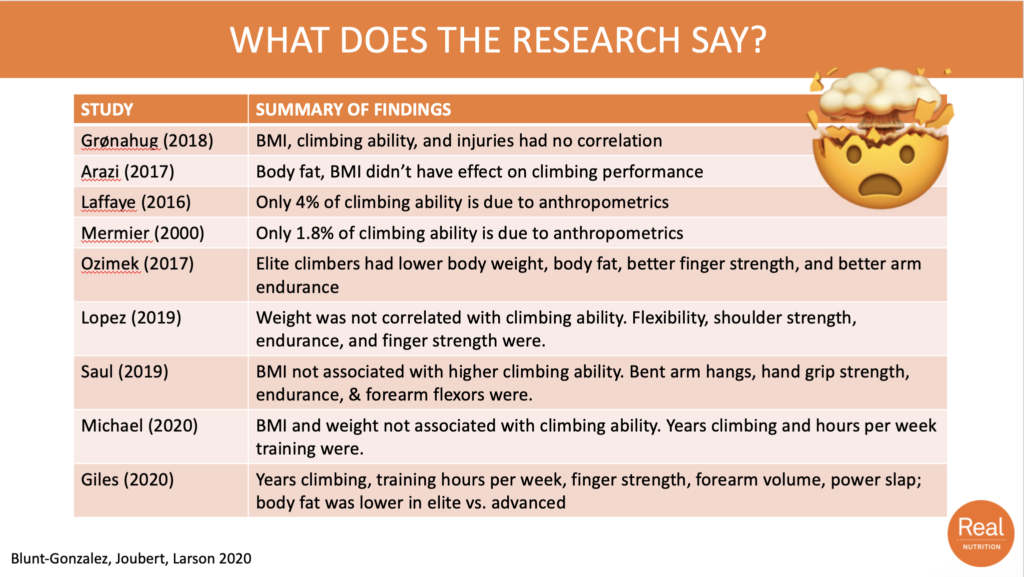

Under-eating can sabotage your health and performance in a number of ways. Many climbers purposefully under-eat, thinking that losing weight or being light will help performance. But this method is fraught with risks and is not supported by scientific evidence.

From my experience working with climbers to leverage their nutrition, most are not eating enough. This is also a common theme in climbing research. Take a look at the studies we have currently that explore climber energy intake and whether it is sufficient.

Dietary intake studies in climbers (Not a single study shows that climbers are eating enough!)

| Study | Main takeaways |

| Zapf (2001) | “Nearly half of them failed to meet the recommendations for top level elite athletes” |

| Sas-Nowosielski (2019) | 48% of the climbers consumed less than 2000 calories daily |

| Simič (2022) | 63% of the climbers failed to get even 30 kcal/kg fat-free mass (the standard is 45 kcal/kg FFM, which no one achieved). 56% did not meet protein requirements. |

| Michael (2019) | 82% of adolescent climbers under-ate their target calorie needs. 86% under-ate their target carbohydrate needs. |

| Chmielewska (2023) | 56% of the climbers had low energy availability (EA). Suboptimal EA was found in 73% of the intermediate climbers, 45% of the advanced, and 40% of the elite female climbers. |

| Mondedero (2022) | 52% of the climbers were in a negative energy balance. 88% had suboptimal EA. |

| Gibson-Smith (2020) | 77% of climbers did not meet their estimated energy requirements. |

| En (2025) | Most climbers ate 80% of estimated energy needs. The majority did not meet estimated protein needs. |

| Úbeda (2021) | Males met only 51% of their energy needs. Females met only 62% of their energy needs. Climbers did not meet protein and carbohydrate requirements. |

| Ueland (2020) | Carbohydrate intake and hydration status play a role in climbing performance. |

| Mashuri (2022) | Researchers assessed climbers’ energy needs based on climbing and other activities, as well as their estimated BMR. They determined that the average target calories for their subjects was 4568 calories, with 685 grams of carbohydrate and 171 grams of protein. |

| Mora-Fernandez (2024) | 56% had sub-optimal energy availability. 36% had low energy availability. 58% ate below carbohydrate recommendations. 31% ate below protein recommendations |

| Okoren (2023) | Overall, climbers tend to under-eat and do not meet target carbohydrate needs. |

| Przeliorz (2022) | Climbers did not meet estimated energy needs to be in a state of adequate energy availability. Most climbers studied did not have an adequate intake of flavonoids (found in antioxidant-rich foods such as fruits and vegetables). |

| Przeliorz-Pyszczek (2019) | Some climbers under-ate their energy and carbohydrate needs. There were correlations with climbing ability and various micronutrients. |

| Merrells (2008) | Climbers did not eat enough on their outdoor trip. They ate about 40% of their estimated needs. |

As you can see, not a single study shows climbers eating adequately!

If you’re wondering if you should lose weight to enhance performance, the answer is probably no. And if you’re wondering if you need to eat more, the answer is probably yes!

For expert one-on-one help, reach out to me for nutrition coaching/counseling. If you want to learn more but don’t need personalized help, try our on-demand course on climbing nutrition.

References

Chmielewska A, Regulska-Ilow B. (2023). The evaluation of energy availability and dietary nutrient intake of sport climbers at different climbing levels. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 5176.

En JASJ, Ramz NHB, Vern YT, Xuan XT. (2025). Body composition and measured energy expenditure in relation to dietary intake among regular climbers in Klang Valley, Malaysia. Sport Sciences for Health https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-025-01369-y

Gibson-Smith E, Storey R, Ranchordas M. (2020). Dietary intake, body composition and iron status in experienced and elite climbers. Frontiers in Nutrition, 7, 122.

Mashuri H, Mappaompo MA, Purwanto D. (2022). Analysis of energy requirements and nutritional needs of rock climbing athletes. Journal Sport Area, 7(3), 437-445.

Merrells, Friel, Knaus, Suh. (2008). Following 2 diet-restricted male outdoor rock climbers: impact on oxidative stress and improvements in markers of cardiovascular risk. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 33:1250-1256

Michael MK, Joubert L, Witard OC. (2019). Assessment of dietary intake and eating attitudes in recreational and competitive adolescent rock climbers: A pilot study. Frontiers in Nutrition, 6, 64.

Monedero J, Duff C, Egan B. (2023). Dietary intakes and the risk of low energy availability in male and female advanced and elite rock climbers. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 37(3), e8-e15.

Mora-Fernandez A, Argüello-Arbe A, Tojeiro-Iglesias A, Latorre JA, Conde-Pipó J, Mariscal-Arcas M. (2024). Nutritional assessment, body composition, and low energy availability in sport climbing athletes of different genders and categories: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients, 16(17), 2974.

Okoren L, Magkos, F. (2023). Physiological Characteristics, Dietary Intake, and Supplement Use in Sport Climbing. Current nutrition reports, 12(4), 788–796.

Przeliorz A, Regulska-Ilow B. (2022). Relationship between the dietary intake of sport climbers according to climbing grading scales and the dietary supply of antioxidants. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 22(3), 795-802

Przeliorz-Pyszczek A, Gołąbek K, Regulska-Ilow B. (2019). Evaluation of the relationship of the climbing level of sport climbers with selected anthropometric indicators and diet composition. Central European Journal of Sport Sciences and Medicine, 28(4), 15-26.

Sas-Nowosielski K, Wycislik J. (2019). Energy and macronutrient intake of advanced Polish sport climbers. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 19, 829-832.

Simič V, Jevšnik Š, Mohorko N. (2022). Low energy availability and carbohydrate intake in competitive adolescent sport climbers. Kinesiology, 54(2), 268-277.

Úbeda N, Carvacho CL, González ÁG. (2021). Energy and nutritional inadequacies in a group of recreational adult Spanish climbers. Archivos de medicina del deporte: revista de la Federación Española de Medicina del Deporte y de la Confederación Iberoamericana de Medicina del Deporte, 38(204), 237-244.

Ueland K, Harris C, Kloubec J, Kirk E. (2020). How diet impacts performance in rock climbers: a pilot study. Current Developments in Nutrition, 4, nzaa066_024

Zapf J, Fichtl S, Wielgoss S, Schmidt W. (2001). Macronutrient intake and eating habits in elite rock climbers. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 33(5):S72.